Vector-based transmission

Mosquito bite

The vector mode of transmission of ZIKV is by a daytime bite (indoors and outdoors) of the Aedes spp. of mosquito. In urban areas, Zika virus is mainly transmitted in a human–mosquito–human cycle.1 Two species of the Aedes – Ae. aegypti and, to a lesser extent Ae. albopictus are linked with most ZIKV outbreaks. Other lesser known species of Aedes like Ae. Hensilii, Ae. africanus, Ae. apicoargenteus, Ae. luteocephalus, Ae vitattus and Ae. furcifer also have the potential of causing ZIKV infections.1

Avoiding mosquito bites is the most crucial measure to prevent ZIKV infection.

This can be achieved by:

- Wearing light coloured clothes, which cover the full body

- Staying indoors with air conditioning

- Using door and window screens to prevent mosquitoes from entering the room

- Sleeping under mosquito nets

- Applying insect repellents like DEET, IR3535 (Ethyl butylacetylaminopropionate) or Icaridin as per the manufacturer’s instructions

- Applying an outdoor/indoor flying insect spray in the resting places of mosquitoes especially dark, humid places like under the sink, in closets, under furniture, and lofts etc.

To control mosquito breeding inside/outside the house, all water storage containers (buckets, drums, pots etc.) should be tightly closed to block all potential egg-laying sites. Local government bodies should undertake cleanliness drives in localities and also spray insecticides regularly to reduce the mosquito menace.

Non-vector-based transmission

-

Sexual transmission

Sexual transmission of ZIKV is also documented in literature, with reports of at least three such cases.2

However, sexual transmission could be easily curbed in the following ways:

- Men living in or travelling from areas where ZIKV is rampant should follow safe sexual practices or abstain from sex altogether

- Condoms should be used for vaginal, anal and oral sex

- ZIKV persists longer in the semen than in blood.4 Hence, safe sex should be practiced for at least 8 weeks by persons returning from ZIKV affected areas even if they are asymptomatic3

- In the event of men who are symptomatic with fever, rash, conjunctivitis, muscle and joint pains, safe sexual practices should be adopted for a minimum of 6 months3

- Couples who plan for pregnancy should wait for 8 weeks before trying to conceive if both partners are asymptomatic. However, should even one of the partners show symptoms of ZIKV infection, conception should be postponed for at least 6 months3

-

Maternal-foetal transmission

ZIKV infection can be transmitted from the mother to the unborn foetus. Intrauterine transmission is supported by the detection of ZIKV in the amniotic fluid of mothers infected with the virus, whose foetuses had cerebral abnormalities as seen in ultrasonography.5 Further, RT-PCR on blood and brain tissue samples taken from neonates born with microcephaly show the presence of ZIKV.6 Breast feeding, though not yet proven, could be another mode of transmission from mother to baby as ZIKV RNA has been isolated in breast milk of infected mothers, albeit, the virus could not be propagated in susceptible cell cultures.2

-

Blood Transfusion

Blood transfusion is another possible non-vector mode of transmission of ZIKV infection. An RT-PCR analysis, conducted during the French Polynesian outbreak in 2013-2014, found that 42 (2.8%) of 1,505 asymptomatic blood donors were positive for ZIKV. Eleven of the 42 donors described a Zika fever-like syndrome 3-10 days after donation.7 The same study also reported two cases of ZIKV infection probably acquired through the transfusion of infected blood.7

Prognosis of Zika virus infection

The incubation period from a mosquito bite to the onset of symptoms is roughly 3-12 days.1 The majority of people with ZIKV infections show subclinical or mild influenza-like illness with fever, headache, rash, joint pain, muscle pain and non-purulent conjunctivitis (red eyes). The disease is usually self-limiting, lasting for ~7 days.1 However, it could cause complications due to its suspected links with neurological disorders and neonatal malformations.

Complications of Zika virus infection

Although complications of ZIKV infections are rare, its global echoes are mostly due to the issues of congenital microcephaly and foetal loss among women infected during pregnancy, as well as neurological complications coupled with Guillain-Barre syndrome (GBS), in adults.

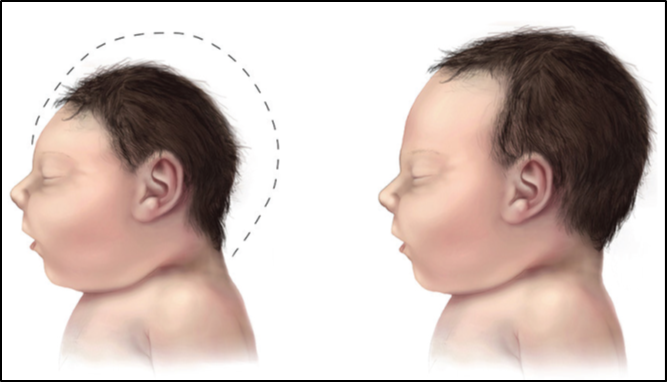

In early 2015, an outbreak of ZIKV infection was identified in north eastern Brazil. By January 2016 there were 3,893 babies born with microcephaly and 49 of these babies died.8 ZIKV was identified in the amniotic fluid of 2 women with foetuses having microcephaly in ultrasound. In a study of 35 infants with microcephaly born during August-October 2015 in Brazil;9 mothers of all 35 had lived in or visited ZIKV-affected areas during pregnancy, 25 (71%) infants had severe microcephaly (figure 1) (head circumference >3 SD below the mean for sex and gestational age).

Figure 1: Infant with microcephaly (left) compared with an infant with a normal head size (right)6

The prevalence of GBS has also increased by 19% in endemic areas of ZIKV infection.10 Several countries in both the Americas have reported an unusual increase in cases of GBS, which coincide with the increase in ZIKV outbreaks.8 In the French Polynesian study of 2013-14, done during the ZIKV outbreak, 42 patients were diagnosed with GBS. Amongst these, 39 (93%) had anti-ZIKV IgM antibodies lending support to a preceding ZIKV infection.7

Diagnosis of ZIKV Infection

ZIKV infection is confirmed using RT-PCR analysis, which detects viral RNA in serum samples during an acute phase of infection. This remains the single most accurate test for the confirmation of ZIKV infection. Antibodies to the virus develop 3-8 days after infection and the ELISA developed by the Arboviral Diagnostic and Reference Laboratory- Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Atlanta, GA, USA) detects immunoglobulin IgM antibodies to ZIKV from serum samples. In case of a positive ELISA, the virus plaque-reduction neutralization test (PRNT) should be carried out to establish whether the positive IgM antibody indicates a recent Zika virus infection or a false-positive result.

Therapeutic Approaches

Around 80% of the people infected are asymptomatic.6 However, those with symptoms, which are usually mild, are treated for them and do not require hospitalization.

Treatment includes:

- Getting plenty of rest

- Drinking fluids to combat dehydration

- Taking antipyretics or analgesics to reduce fever and pain

- Aspirin and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) are recommended only after dengue is ruled out. This is to reduce the risk of bleeding

There is no known drug to treat ZIKV infection or a vaccine for preventing the disease. Ranpirnase, an anti-cancer compound has been investigated for its antiviral activity in a cell-based model, where it inhibited ZIKV compared to the control.6 Another cell-based study in France showed that ZIKV is sensitive to both types of Interferons I and II.6 The lack of animal models to demonstrate in vivo activity is a major obstacle for drug development.

Laval University in Quebec, Canada have announced a Zika Vaccine, which could be available for emergency use as early as October/November 2016; although the regulatory approvals may take much longer. Hawaii Biotech Inc. started a trial to test its ZIKV vaccine in 2015. Inovio Pharmaceuticals created a DNA-based vaccine and plan to do a Phase1 clinical trial in humans by the end of 2016. Indian biotech company Bharat Biotech has two ZIKV vaccines undergoing pre-clinical trials; one is a recombinant one, while the other is an inactivated one. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) has also proposed two vaccines: a DNA-based and a live-attenuated one. Other major pharmaceutical companies like Pfizer, Johnson & Johnson, Sanofi, Takeda and Merck are also joining the vaccine race.2 Thus, although there are no drugs or vaccines currently, the area is rapidly evolving with potential therapies available in the near future.

References

- Plourde, A. R., Bloch, E. M. A Literature Review of Zika Virus. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 22, 1185-1192 (2016).

- Saiz, J-C., Vázquez-Calvo, A., Blázquez, A. B., Merino-Ramos, T. et al. Zika Virus: the Latest Newcomer. Frontiers in Microbiology. 7, Article 496 (2016).

- Zika virus. World Health Organization. (2016)

- Prevention| Zika virus | CDC. (2016). Cdc.gov.

- Oliveira Melo, A. S., Malinger, G., Ximenes, R., Szejnfeld, P. O. et al. Zika virus Intrauterine infection causes fetal brain abnormality and microcephaly: tip of the iceberg? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 47, 6–7 (2016).

- Fellner, C. Zika Virus: Anatomy of a Global Health Crisis. P & T. 41, 242-253 (2016).

- Musso, D., Nhan, T., Robin, E., Roche, C., Bierlaire, D. et al. Potential for Zika virus transmission through blood transfusion demonstrated during an outbreak in French Polynesia,November 2013 to February 2014. Euro Surveill. 19, 20761 (2014).

- Lee, J. Zika Virus Infection: New Threat in Global Health. Korean Med Sci. 31, 331-332 (2016).

- Schuler-Faccini, L., Ribeiro, E., Feitosa, I., Horovitz, D., Cavalcanti, D. et al. Possible Association Between ZikaVirus Infection and Microcephaly. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 65, 59–62 (2016).

- Zika Situation report. Neurological Syndrome and Congenital Anomalies.